Seven Days in June

A multimedia story based around the final diary entries of North Vietnamese doctor, Dang Thuy Tram, in June 1970.

By Rupert Bedford.

Published on Dec 20, 2021

Animations by May Kindred-Boothby.

Diary Narrations (in English) by Crystal Yu.

An improvised operating room in the jungle during the war in Viet Nam. © Vo Anh Kanh

On December 23, 1966 a young newly qualified North Vietnamese doctor boarded a truck in Hanoi with a group of civilians — journalists, photographers and doctors — and headed down to a staging post in Quang Binh Province. From there she and her companions trekked south on foot for three arduous months down what became known by the Americans as the Ho Chi Minh Trail through the mountains of the Truong Son range. Her destination was Duc Pho district in Quang Ngai province, a frontline area where fighting with American forces was intensifying. There she was assigned as chief medical officer to a field clinic. She was 24 years old and her name was Dang Thuy Tram.

By June 1970, advances by the American forces meant that Thuy was confined to the jungle, operating out of temporary clinics and constantly on the move.

Day 1— 2nd June 1970.

Thuy Tram as a student in Hanoi, 1958

Before becoming a doctor to serve the war effort, Thuy’s inclination when growing up was to become a writer.

During the war, despite the terrible conditions, she managed to keep a diary of her thoughts, feelings and experiences on the frontline. On a number of occasions she reveals how her letters home to her family only tell half the story.

Day 2–10th June 1970.

Thuy was the eldest of five children — four girls and a much younger boy. Her father was a surgeon at St.Pauls Hospital, her mother a lecturer at the Hanoi School of Pharmacology and one of the leading experts on the use of Vietnamese medicinal plants. Thuy and her siblings used to hang around the botanical garden at the school, learning about the plants and their uses. And during the war she used this knowledge to train the local people in Duc Pho how to grow medicinal herbs and turn them into medicine for treating patients.

Day 3–16th June 1970.

Thuy’s analogy of being ‘as tense as a taut guitar string’ comes from her love of music. Her father used to play western classical music to relax after surgery and she learned to play violin and guitar. She often played to her patients to distract them from their pain.

Thuy playing guitar in Pho Cuong, Duc Pho District 1968

Despite being a newly qualified medic when she arrived in Duc Pho, Thuy set about establishing a network of clinics in the area and trained up nurses to carry out basic medical procedures. She carried out surgical operations herself in the field, often without the aid of anaesthetic.

By June 1970 Thuy’s makeshift medical clinics in the jungle were being regularly bombed by helicopters and aircraft. And she was aware that her situation was becoming increasingly precarious. But Thuy’s primary concern was for her patients, whom — we have learned from her wartime colleagues — she cared for as if they were her own children.

Day 4–17th June 1970.

In her diary Thuy often writes of her yearnings for the North and returning home to reunite with her family. She retains this hope right until the end.

In the following passage, Thuy observes that ‘not a single bird chirps’ — The bombs and chemical defoliants used during the war decimated the bird populations of Viet Nam. Many Vietnamese commented on the eerie quiet, and on how sad they felt in the absence of birdsong.

Day 5–18th June 1970

The last known photograph of Thuy — in Pho Cuong, Duc Pho District, 1968

On 20th June 1970 Thuy makes her final diary entry.

Feeling frightened and abandoned she bids a tearful farewell to two of her medical colleagues who are forced to leave the clinic to seek help. She ends with a childlike plea to her mother for the love and strength to help her prevail on the ‘perilous road’ before her.

Day 6–20th June 1970

Day 7…

On the morning of June 22, 1970, soldiers from a company of the Americal Division heard the sound of “a radio playing VN music and voices of people talking” while out on patrol.

Later that day, the 2nd Platoon spotted four people moving toward them down a jungle trail. One of them was Dr. Dang Thuy Tram, dressed in black pants and a black blouse, and wearing Ho Chi Minh sandals.

The Americans opened fire, killing Thuy and a young NVA soldier named Boi. “The other two evaded off the trail and were lost by the element,” according to the after-action report.

Discovered among Thuy’s possessions were a Sony radio, a rice ledger, a medical notebook with drawings of the wounds she treated, bottles of Novocain, bandages, poems written to an NVA captain along with his photograph

— and a diary.

The Diary’s Return

Thirty five years later, in April 2005, a package was delivered to Thuy’s mother Doan Ngoc Tram at her home in Hanoi.

It was a copy of Thuy’s diary.

Diary of Dang Thuy Tram

The package had been sent by Fred Whitehurst, a lawyer who had served with a military intelligence detachment at the Americal’s base in Duc Pho. In 1970, Whitehurst had saved Thuy’s surviving diaries from being destroyed after his interpreter, Sergeant Nguyen Trung Hieu had said to him “Don’t burn this one Fred. It has fire in it already”. Against regulations he took the diaries home with him when he left in 1972, after serving three tours in Viet Nam.

Fred Whitehurst in Vietnam

The diaries went into a filing cabinet and stayed there while he took a doctorate in chemistry and joined the FBI as a forensic scientist. Whitehurst often thought of trying to return them to Thuy’s family, but he had no idea how to find the family, and as an FBI agent, he could hardly approach officials in the Vietnamese embassy.

In the mid 1990’s he became a celebrated whistleblower, exposing corruption and incompetence in FBI investigations. And after he quit he began to think about the diaries again. With the help of his brother Robert over many years, Fred was eventually able to have the diaries translated and finally trace Thuy’s family in Hanoi. By this time the diaries had been entrusted for safekeeping to the Vietnam Centre at Texas Tech University, and arrangements were made for the Tram family to visit the US to view the diaries for the first time.

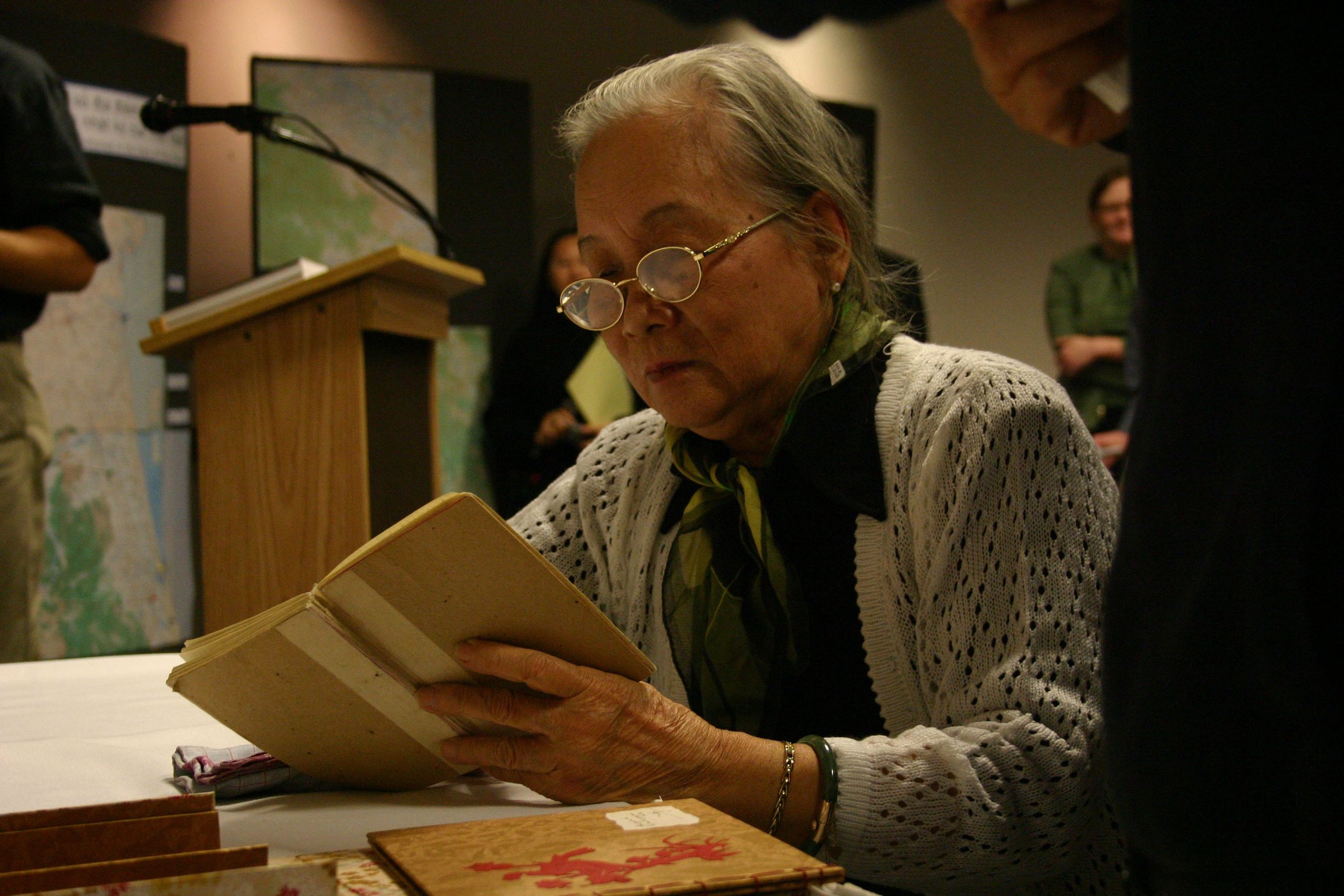

Thuy’s mother Doan Ngoc Tram viewing the original diaries for the first time. © Vietnam Center, Texas Tech University

Doan Tram and her family had been shocked and surprised when they discovered the existence of Thuy’s diaries. After the war ended in 1975 they had visited Duc Pho a number of times and had been told that none of Thuy’s belongings had survived the war. They describe seeing the diaries for the first time as a ‘mixed blessing’.

Doan Tram — “It was both painful and joyful. I hugged that diary and it seemed like I was holding my daughter.”

The Whitehurst brothers went on to develop a close relationship with Doan Tram and her family and, following a number of visits to Viet Nam, were welcomed as adopted members of the family.

Doan Tram — “I was very happy and welcomed them and was grateful to them. Thanks to them my daughter could relive, so that she could be known and live in the hearts of many people”.

Fred Whitehurst with Thuy’s mother Doan Tram at her home in Hanoi. © Neil Alexander

Robert (left) and Fred Whitehurst with the Tram family in Hanoi. © Neil Alexander

Thuy’s diaries were published in Hanoi on July 18th 2005 and generated huge interest in Viet Nam. It seems they struck a particular chord among young readers. Two-thirds of all Vietnamese were born after 1975, and for them the war was ancient history, and a history taught in a dry, stylized fashion. Other war diaries had been published, but, like the textbooks, they spoke mainly of heroism and great victories. Thuy’s diaries broke the mould. Here was a brave, idealistic young woman, but one with vulnerabilities and self doubts; a romantic in spite of all her discipline.

The diaries have since been translated into many languages and published around the world.

Thuy Tram was one of millions killed or injured during the war in Viet Nam. © Rupert Bedford

Between 1955 and 1975, it is estimated that over 2 million Vietnamese civilians were killed. Many families still wait to be reunited with the remains of their loved ones.

Over 4 million Vietnamese citizens have been exposed to the chemical herbicide known as Agent Orange. Many continue to suffer serious disabilities and health problems.

The environmental destruction caused by Agent Orange was referred to as ‘ecocidal’ warfare and sparked a debate in the early 1970’s that eventually led to the inclusion of Ecocide as an international war crime.

Unexploded ordnance has killed over 40,000 people since the end of the war. It continues to detonate and kill people today.

______________________

*Day 7 Extract courtesy of Last Night I Dreamed of Peace, (Penguin Random House)

Rupert Bedford is a UK based journalist and documentary maker — with Vietnamese relatives. This project is the result of visits to Viet Nam made by Rupert in 2018/19 including conducting interviews with Thuy’s mother Doan Tram in Hanoi and Thuy’s wartime nursing colleague Ta Thi Ninh in Duc Pho.

© RB Media.

If you are interested in publishing this story please contact Rupert at rupert.bedford@rbmedia.org